|

For further information, contact the MBL Communications Office at (508) 289-7423 or e-mail us at comm@mbl.edu

For Immediate Release: August 16, 2011

Contact: Carol Schachinger, The Biological Bulletin, 508-289-7149, cschachi@mbl.edu

Regenerative Powers in the Animal Kingdom Explored in Special Issue of The Biological Bulletin

|

|

|

Resources

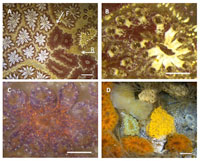

Sea Squirt: The sea squirt is familiar as a pest that clumps to the bottom of docks and boats. Its powerful regenerative capacities are analyzed by Robert Lauzon and colleagues in the August issue of The Biological Bulletin. These colonies (Botryllus schlosseri) were collected in Woods Hole, Mass. Credit: Robert Lauzon

Zebrafish: The zebrafish is capable of fin and heart regeneration. Credit: Lukas Roth

African clawed frog (Xenopus laevis): The frog exhibits limb and lens regeneration. Credit: A. Turner (Atlas and Red Data of the Frogs of South Africa, Lesotho and Swaziland)

|

WOODS HOLE, MA—Why can one animal re-grow tissues and recover function after injury, while another animal (such as a human being) cannot? This is a central question of regenerative biology, a field that has captured the imagination of scientists and the public since the 18th century, and one that is finally gaining traction and momentum through modern methods of analysis.

Regeneration of the eye lens in frogs; of neural tissue in the snail; of the spinal cord in the sea lamprey; of the entire viscera in the sea cucumber—these and other capacities of animal regeneration are detailed in a “virtual symposium” in this month’s issue of The Biological Bulletin.

“[The] use of animal models to understand the mechanism of regeneration is both fruitful and of potentially enormous significance to the future practice of medicine,” write the issue’s co-editors, Joel Smith of the MBL’s Eugene Bell Center for Regenerative Biology and Tissue Engineering; and James L. Olds of the Department of Molecular Neuroscience at George Mason University.

“The challenge is to describe the mechanisms of (animal) regeneration at the molecular level, delivering detailed insights into the many components that are cross-regulated,” assert Smith and colleagues in a research article that advocates a “systems” approach of constructing maps of gene activity during the animal’s regenerative phase.

The power of this approach, they write, is that studying regeneration in a carefully selected model (spinal cord regeneration in the sea lamprey, for example) “can reveal gene regulatory networks that may be conserved in the human central nervous system and may therefore serve as therapeutic targets for new pharmacological and biological compounds after brain or spinal cord injury.”

Other authors take different approaches to illuminating regenerative biology. Robert Lauzon of Union College and colleagues, in research conducted partly at the MBL, consider the roles of stem cells and allorecognition in sea squirt regeneration. Nozomi Yoshinari and Atsushi Kawakami of Tokyo Institute of Technology review the process of fin regeneration in zebrafish and medeka and highlight the “compartments” or subpopulations of cells that are involved. MBL scientists Mark Messerli and David Graham review the roles of extracellular electrical fields (EFs) in controlling development, wound healing, and regeneration. Three of the issue’s papers apply tools and insights from neuroscience to investigate neural regeneration in the snail (Ryota Matsuo and Esturo Ito of Tokushima Bunri University; M.J. Zoran of Texas A&M and colleagues; and in the sea squirt (H.N. Sköld of University of Gothenburg and colleagues). Finally, the issue reprints a landmark article on the concept of polarity in regenerative processes by Thomas Hunt Morgan, an early leader in the field, which was first published in The Biological Bulletin in 1909.

In co-editing the issue, Smith and Olds write, “we were struck anew how many unanswered questions of basic science are central to regeneration,” such as the “age-old question [of] whether, and to what degree, regenerative processes recapitulate the developmental program.” But the field of regeneration today is “broad and vibrant,” as this issue of The Biological Bulletin shows, with many efforts furnishing answers and clues.

The Biological Bulletin publishes outstanding experimental research in the areas of invertebrate neurobiology, comparative aspects of developmental biology, functional morphology and biomechanics, and aspects of comparative physiology and physiological ecology, such as symbiosis. It publishes peer-reviewed research papers, rapid communications, position papers, and invited review articles and symposia, six times a year. Published since 1897 by the Marine Biological Laboratory (MBL) in Woods Hole, Massachusetts, The Biological Bulletin is one of America’s oldest peer-reviewed scientific journals. It is aimed at a general readership and especially invites articles about those novel phenomena and contexts characteristic of intersecting fields. The electronic version, Biological Bulletin Online, contains the full content of each issue, including all figures and tables, beginning with the February 2001 issue. PDF files of the entire archive from 1897-2000 are also available.

The Marine Biological Laboratory (MBL) is dedicated to scientific discovery and improving the human condition through research and education in biology, biomedicine, and environmental science. Founded in 1888 in Woods Hole, Massachusetts, the MBL is an independent, nonprofit corporation.

|