|

For further information, contact the MBL Communications Office at (508) 289-7423 or e-mail us at comm@mbl.edu

For Immediate Release: March 26, 2009

Contact: Diana Kenney, MBL, 508-289-7139; dkenney@mbl.edu

|

|

|

Resources:

Photos:

Click on thumbnails for full size images.

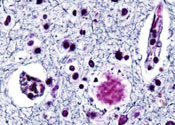

Histopathologic image of senile plaques seen in the cerebral cortex in a patient with presenile onset of Alzheimer’s disease.

Loligo pealeii (Longfin inshore squid) Photo credit: Roger Hanlon

Citations:

Pigino, G., et al. (2009) Disruption of fast axonal transport is a pathogenic mechanism for intraneuronal amyloid beta. PNAS: doi 10.1073/pnas0901229106.

Read the full article (pdf format)

Moreno, H. et al. (2009) Synaptic transmission block by presynaptic injection of oligomeric amyloid beta. PNAS: doi 10.1073/ pnas09000944106.

Read the full article (pdf format)

Background information:

Lapointe, N.E., et al. (2009) The amino terminus of tau inhibits kinesin-dependent axonal transport: Implications for filament toxicity. J. Neurosci. Res. 87(2): 440-451.

|

Tiny But Toxic

MBL researchers discover a mechanism of neurodegeneration in Alzheimer’s disease

WOODS HOLE, MA—Tiny, toxic protein particles severely disrupt neurotransmission and inhibit delivery of key proteins in Alzheimer’s disease, two separate studies by Marine Biological Laboratory (MBL) researchers have found.

The particles are minute clumps of amyloid beta, which has long been known to accumulate and form plaques in the brain of Alzheimer’s patients.

“These small particles that haven’t aggregated into plaques—these are increasingly being seen as the really toxic species of amyloid beta,” says Scott Brady of University of Illinois College of Medicine, who has been an MBL investigator since 1982.

Brady and his colleagues found that these particles inhibit neurons from communicating with each other and with other target cells in the body.

“The disease symptoms for Alzheimer’s are associated not with the death of the neurons – that is a very late event – but with the loss of functional connections. It’s when the neuron is no longer talking to its targets that you start to get the memory deficits and dementia associated with the disease,” Brady says.

The amyloid beta particles activate an enzyme, CK2, which in turn disrupts the “fast axonal transport” system inside the neuron, Brady found. This transport system has motor proteins that move various kinds of cargo (including neurotransmitters and the associated protein machinery for their release) from place to place in the neuron on microtubule tracks.

Brady’s findings are complemented by a new study by Rudolfo Llinás of New York University School of Medicine. Brady and Llinás both conduct neuroscience research at the MBL using the giant nerve cell of the Woods Hole squid, Loligo paeleii, as a model system.

Llinás found that activation of CK2 blocks neurotransmission at the synapse – the point where the neuron connects to its target.

“Disruptions in the fast axonal transport system are probably key elements in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s and other adult-onset neurodegenerative diseases, such as Parkinson’s and ALS,” says Brady. “It doesn’t mean that is the only thing going on, or that it is the triggering feature of the disease. But we do know that changes in the fast axonal transport system are sufficient to cause the ‘dying back’ of neurons that is characteristic of these diseases.”

The new findings suggest the possibility of designing a drug to inhibit CK2 activation in Alzheimer’s patients. However, a prior study by Brady found that activation of another enzyme, GSK3, in Alzheimer’s also disrupts the fast axonal transport system. It may therefore be necessary to inhibit both enzymes.

“There haven’t yet been any therapies designed for Alzheimer’s with the idea of protecting the fast axonal transport system,” says Brady. “But if there were, they would have to inhibit the activation of both CK2 and GSK3. We can’t think of it as a single thing going wrong. There are several things going wrong.”

The MBL is a leading international, independent, nonprofit institution dedicated to discovery and to improving the human condition through creative research and education in the biological, biomedical and environmental sciences. Founded in 1888 as the Marine Biological Laboratory, the MBL is the oldest private marine laboratory in the Western Hemisphere. For more information, visit www.MBL.edu.

|