|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

June 20, 2008

Grass Fellow Shines (Polarized) Light on Honeybee Controversy

By Joseph Caputo

|

|

|

Photos

Please click on thumbnails for full-sized images:

Dr. Keram Pfeiffer, a 2008 Grass Fellow, feeds a bee sugar water in preparation for a conditioning experiment. Credit: Joseph Caputo/MBL

Honeybees are collared so they cannot move around during the experiment, which addresses an ongoing controversy on how bees recognize polarized light. Credit: Joseph Caputo/MBL

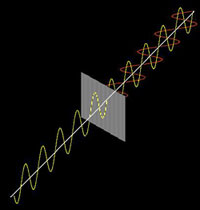

Light is polarized if it vibrates in one direction. Here only the light wave moving in a up-down direction can pass through the filter. Credit: Keram Pfeiffer

Video:

Bee Conditioning (.wmv format)

After viewing the UV polarized light, a honeybee sticks out its proboscis to suck up its sugar water reward. Credit: Keram Pfeiffer

|

MBL, WOODS HOLE, MA—Keram Pfeiffer ends his days in the Grass Laboratory at the MBL by feeding his honeybees. Each less than an inch in length, they fidget as Pfeiffer fills a pipette with their meal of sugar water. He then chooses a bee from the plastic case where they’re packed side-by-side, their heads poking out of tubes. Pfeiffer steadies a bee with his left hand and with his right, gently touches the pipette to the sensitive tip of the insect’s tongue.

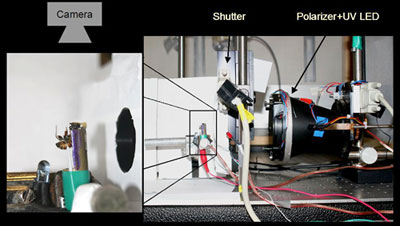

These feedings are essential for Pfeiffer’s first attempt at a behavioral experiment. The next morning, the now hungry bee is placed in a boxed compartment that faces an LED lamp. The lamp radiates UV light, which is invisible to humans but recognized by bees and other insects. The light travels through a polarization filter, which causes the light waves to vibrate in one direction. Because the blue sky shows a pattern of this directional light, bees can to deduce the location of the sun, even if it is hidden behind a veil of clouds.

Four seconds after the LED flashes, Pfeiffer gives the bee another treat.

“That's Pavlovian reward,” Pfeiffer says. “I hope the bee will learn that the polarized light stimulus will predict the sugar water reward. So after a couple of trials, it will extend its proboscis,” the long, tongue-like appendage honeybees use to collect food.

Pfeiffer received a fellowship from the Grass Foundation to spend his summer at the MBL. While here, he hopes to renew interest in a decades-old controversy over whether honeybees see polarized light instantaneously or if they need to scan their surroundings first.

“There is no direct evidence for one or the other,” Pfeiffer says. “Since the 70s, both theories have had people doing behavioral experiments, but the animals were free range and moving. The conclusions they drew were indirect.”

Pfeiffer’s experiment is different because his bees are stationary when they view the polarized light. In order to keep the bees in place, he fastens a collar between each insect’s head and thorax. Two groups of bees will be trained. The first group will be exposed to the light directly. In the second group, the polarized light will rotate 180 degrees above the bee during each trial. Every bee will undergo 10 trials a day.

If only the bees in the first group can be conditioned, it’s evidence that insects do not need to scan the sky before locating a hidden sun. Either result would be a clue to understanding how polarized light sensing evolved in insects.

Pfeiffer’s research is a continuation of work he began as a doctoral student at the University of Marburg in Germany. It was there he earned a Ph.D. in neurobiology for describing how neurons in the locust brain activate in response to polarized light. In addition to the conditioning experiments, Pfeiffer plans to obtain comparative data with bees. Although he feels more at home with experiments at the cellular level, he believes there are different questions science can answer with behavior.

“I'm really excited about it,” Pfeiffer says about his first time working with bees, which he obtained from private keepers in Woods Hole. “I just started, so it can absolutely be they just don't learn at all.” He is confident though, as another team of scientists were able to condition bees to respond to green light after 20 trials in 2006. “It’s not an easy thing to do,” he adds. “If something comes out of it, great. If not, that's all right too. I appreciate the environment at the MBL because it gives me lots of support to try risky experiments.”

The experimental setup. The bee is held in a boxed compartment, waiting for the LED lamp to shine. Credit: Keram Pfeiffer (click for full size image)

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|