|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Return to Table of Contents

|

|

Mitchell Sogin

|

|

Counting Microbes and Making them Count

MBL scientists lead international effort to unveil the ocean’s hidden majority

Anyone familiar with famed astronomer Carl Sagan knows there are “billions and billions” of stars in the sky. Now, thanks to an initiative to catalog all of Earth’s known marine organisms, the world will someday know how many billions of microbes live in our oceans and just how important they really are.

The MBL-led International Census of Marine Microbes (ICoMM) is the first global effort to study the vast biodiversity of the world’s smallest marine organisms, creatures often taken for granted because they aren’t visible to the naked eye.

|

|

|

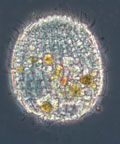

Microbes Revealed

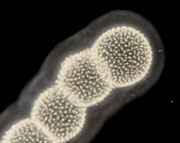

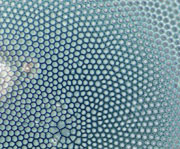

Like precious jewels, marine microbes come in a dazzling array of shapes and colors. They also perform critical functions in the marine ecosystem. Here is a microscope’s-eye view of some of these unsung simple organisms. To see these and other microbes in living color, visit micro*scope, an ICoMM-sponsored online database of thousands of images accessible here.

Images courtesy of micro*scope

|

|

|

|

Sphaerellia

|

|

|

|

Beggiatoa

|

|

|

|

Coleps

|

|

|

|

Unidentified ciliate

|

|

|

|

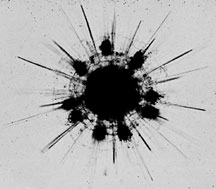

Spumellarida

|

|

|

|

Diatom shell

|

|

The International Census of Marine Microbes project is supported with a seed grant from the New York-based Alfred P. Sloan Foundation, established in 1934 by Alfred Pritchard Sloan, Jr., then president and chief executive officer of the General Motors Corporation.

|

The project is the brainchild of Mitchell L. Sogin, director of the MBL’s Josephine Bay Paul Center for Comparative Molecular Biology and Evolution. He and Jan W. de Leeuw, a senior scientist at the Royal Netherlands Institute for Sea Research, are the project’s leaders. The ICoMM is part of the Census of Marine Life, “a massive worldwide effort to explain the diversity, distribution, and abundance of marine life in our oceans—past, present, and future.”

When it first began, the Census of Marine Life paid minimal attention to microbes—an oversight that concerned Sogin, given his knowledge that 90 to 98 percent of the marine biomass is comprised of these relatively simple organisms. “The real diversity of the ocean is beyond what the eye can see,” he says. “There are approximately one hundred thousand microbes per milliliter of seawater and one hundred million bacteria per gram of sediment in our oceans.”

But the staggering number of marine microbes is just part of their appeal. “We are totally dependent on them for our existence,” says Sogin. “They are the engines of our biosphere, they are the primary catalysts of energy transformation, they are important to the food web, and we need to understand how they work.”

So Sogin proposed the ICoMM, and received $900,000 in seed funding from the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation (the primary funder of the Census of Marine Life), and the project joined a dozen other Census of Marine Life research efforts currently underway. Yet unlike the other initiatives, which focus on geographical locations or restricted environments, the ICoMM has embraced a comprehensive strategy to explore the diversity and distribution patterns of marine microbes everywhere.

Since it launched this past November, the ICoMM has already brought together more than 29 scientists from the U.S., Germany, Chile, Japan, and Spain. “Our goal is to report what is known, what is unknown but knowable, and what may never be known about the biodiversity of marine microorganisms by 2010,” says Sogin.

Besides cataloging existing microbes and discovering new ones, Sogin and his colleagues hope the ICoMM will shed light on our understanding of the evolutionary and ecological processes that create and maintain marine microbial diversity.

The project’s timing is perfect. Though microbes have existed for over three billion years, recent discoveries in molecular science have helped scientists understand these organisms on a genetic level. The work has advanced the science of microbiology by leaps and bounds, and is at the heart of the ICoMM.

Over the next two years, the project’s organizers will build the framework for their mammoth undertaking. Sogin and de Leeuw have already assembled an advisory committee and three interdisciplinary working groups of marine microbiologists, geochemists, molecular evolutionists, and database specialists, who will develop research priorities and experimental plans. The MBL team has also begun work on an online marine microbe database, which will help organize and manage the unprecedented volume of morphological and molecular data the microbe census will produce.

Once the census groundwork is complete, Sogin and his colleagues plan to support pilot projects intended to shape larger-scale research initiatives in marine microbial diversity—projects they hope will attract public and private funding. “Our activities by 2010 will be proportional to available resources,” Sogin says, estimating that ICoMM projects may ultimately cost “from tens of millions to multiple billions of dollars.”

The effort will be well worth it. “Understanding the diversity of marine microbes is a mega-science problem that requires new approaches to mapping diversity, grand strategies, integration of diverse communities, and enabling studies that will explore ecological and evolutionary processes,” says Sogin. “A problem of this magnitude requires careful planning and international cooperation.”

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|