| |

PHYLUM NEMERTEA (NEMERTINEA, NEMERTINI, RHYNCHOCOELA)

Ray Gibson

School of Biological and Earth Sciences, Liverpool John Moores University

Byrom Street, Liverpool L3 3AF, U.K.

Introduction

Nemerteans are often both common and abundant, but because of the difficulties involved in their identification and taxonomy they remain one of the most poorly studied of invertebrate groups. Typically nemerteans are long and slender, ranging from a few millimeters (Carcinonemertes, Prostoma, Tetrastemma) up more than 50 cm (Cerebratulus, Lineus). The longest species known, with a reported length of about 30 m, is Lineus longissimus from European waters, although several Baseodiscus and Cerebratulus species with lengths of more than 2-3 m have been found. Body length, width and general shape are often variable; a specimen only 1-2 mm wide when stretched out over a rocky surface may easily contract to half its original length and a width of 5-6 mm if disturbed. Some of the larger Cerebratulus may be 20-25 mm wide, their dorsoventrally flattened bodies allowing them to swim with up and down undulatory movements. One genus, the bdellonemertean Malacobdella, whose members live in the mantle cavity of bivalve molluscs, is atypical in possessing a leech-like, oval, flattened body with a ventral posterior sucker.

Major anatomical features of nemerteans are that they possess a gut with separate mouth and anus, a closed blood system of thin-walled lacunae or thicker-walled vessels, a well-developed nervous system with lobed cerebral ganglia and paired longitudinal nerve cords, a ciliated epidermis and gut wall and, in most types, a protonephridial excretory system. Their most remarkable feature, however, is their eversible muscular proboscis, housed when retracted in a fluid-filled tubular chamber, the rhynchocoel, which extends along the body above the gut. The higher classification of the phylum into the two classes, Anopla and Enopla, is primarily based upon proboscis morphology. In the Anopla the proboscis is regarded as unarmed, although in many species its epithelium bears batteries of rhabditoid barbs which help in gripping prey, whereas in the Enopla the proboscis is both regionally differentiated and armed, its middle portion (the stylet bulb) containing the armature which consists either of a single needle-like stylet carried on a cylindrical basis (superorder Monostilifera) or a pad- or shield-like basis bearing several small stylets (superorder Polystilifera). A further distinction between anoplan and enoplan nemerteans is that in the former the proboscis pore and mouth are quite separate, the mouth opening below or behind the brain, whereas in the majority of enoplans the mouth and proboscis share the same opening in front of the brain. The long-held view that nemerteans are acoelomate has been rejected in the light of ultrastructural and molecular studies and some authors, such as Scheltema (1993), regard the embryological development of the mesoderm in nemerteans, molluscs, annelids and sipunculans as homologous, whereas others relate nemerteans to protostome coelomates (e.g., Mackey et al., 1996; Zrzav_ et al., 1998).

Although some freshwater or terrestrial forms are known, most species of nemerteans are free-living in marine habitats, either as benthic members of the intertidal and shallow subtidal or as inhabitants of deep-water bathypelagic zones. Some of the benthic marine forms live commensally with a variety of invertebrates, one probable endoparasitic species (Nemertoscolex parasiticus) lives in the coelomic fluid of echiuroids and Carcinonemertes species are variously regarded as specialist egg-predators or ectosymbionts of decapod crabs.

The collection and identification of nemerteans requires care. Often their fragile bodies break during handling and only fragmented or incomplete specimens are obtained; the delicate, tail-like caudal cirrus of Cerebratulus and Micrura species is often lost during collection. A careful examination of living examples is necessary, and the use of muscular anaesthetics such as 7.5% MgCl2 is useful; most species will recover from the effects of anaesthesia when they are returned to clean seawater. Features which are often distinguishable in live material include the number and position of the ciliated cephalic grooves, furrows or slits, eye number and distribution, the shape of the cephalic region (e.g., rounded, pointed, lobed), and body color (e.g., distinct patterns, differences between dorsal and ventral surfaces or anterior and posterior regions). In darkly colored species some of these features may be difficult to distinguish, but in pale colored or almost transparent specimens internal organs such as the proboscis armature, brain lobes, intestine, gonads and rhynchocoel can often be seen. Lightly flattening a specimen between glass slides often aids the examination of internal structures, but extreme care must be taken to avoid bursting the body.

Ultimately, the final identification of most nemertean species depends upon the use of time-consuming histological procedures to study their internal morphology; such procedures are both beyond the scope of the key provided below and not readily available to collectors. Apart from the illustrated key given below, several other references may be of interest to students of nemerteans. Coe's (1943) monograph provides an excellent general biology of the nemerteans of the Atlantic coast of North America, although some of the species names are no longer valid. Miner’s (1950) field guide includes reference to several common species. Kirsteuer (1967) and Gibson (1994) describe how to collect and preserve nemerteans, and Gibson's (1972) reference text provides a broad overview of the biology of these interesting animals.

Check List of Nemerteans of the Woods Hole Region

Species marked with * have not yet been recorded from Woods Hole but may occur in the area. The higher classification given for the phylum follows that proposed by Sundberg (1991).

CLASS ANOPLA

Subclass Palaeonemertea

Carinoma tremaphoros Thompson, 1900

Intertidal and subtidal in sand, sandy mud, mud or clay, less often under stones, typically found in harbors or estuaries. Common in the Woods Hole region, with a range extending to the Atlantic and Gulf coasts of the USA (Cape Cod to Florida and westwards to Louisiana)

* Carinomella lactea Coe, 1905

Mid-shore intertidal to subtidal depths of 20 m or more, burrowed in sand or beneath stones. Originally described from California by Coe (1905) but subsequently dredged from Biscayne Bay, Florida (Corrêa, 1961) and from sand or muddy-sand in Chesapeake Bay (McCaul, 1963) and the Hampton Roads area of Virginia (Boesch, 1973). Not yet recorded from the Woods Hole area.

Cephalothrix linearis (Rathke, 1799)

Intertidal to subtidal depths of 16—18 m or more, in clean, coarse sand, muddy sand or mud, among algal holdfasts or in seagrasses, under stones and boulders, or between mussels and other colonial organisms. Common mid-tidally in the Woods Hole region, with a wide geographic distribution ranging from the Mediterranean and western coasts of Europe to Greenland and the Atlantic coast of North America north of Cape Cod; the species has also been reported from Japan.

Procephalothrix spiralis (Coe, 1930)

Intertidal to subtidal depths of 20 m or more underneath stones, among mussels or other growths, or in sand, mud or clay, often in sediments containing decaying organic material. Common in the Woods Hole region, this gregarious species occurs both on the eastern (Nova Scotia to Long Island) and western (Alaska to southern California) coasts of North America.

Tubulanus pellucidus (Coe, 1895)

Intertidal to subtidal depths of 20 m or more, living in parchment-like tubes among bryozoans, hydroids, ascidians, algae and other growths under stones or in shelly substrata. Not very common in the Woods Hole region, but with a range extending from New England to Florida on the eastern seaboard, and on the western coast of California from San Diego to Monterey Bay.

Subclass Heteronemertea

Cerebratulus lacteus (Leidy, 1851)

Intertidal to subtidal, burrowed in mud, sandy mud, sand or among empty shells or under stones, sometimes found in sheltered bays, harbors and estuaries. The largest of the Woods Hole nemerteans, common in many localities between Maine and Florida including several in the Woods Hole region, but also occurring off the coast of Texas. The species has been widely used for both embryological and toxicological studies.

Cerebratulus marginatus Renier, 1804

Most commonly found subtidally at depths down to 150 m or more, rarely lower shore intertidal, in sand, mud or gravel; it may be found actively swimming at night. The complicated synonymy of this species leads to considerable uncertainty about its zoogeographic distribution, but it has supposedly been found on the Atlantic seaboard of North America from Labrador and Cape Cod southwards under the off-shore Arctic current. Coe (1943) records the species as being found intertidally on the Maine coast and in the Woods Hole area, and subtidally off Gay Head and Block Island.

Fragilonemertes rosea (Leidy, 1851)

Previously recorded from the Woods Hole region as Micrura leidyi (Verrill, 1892)by Coe (1943) but redescribed by Riser (1998) and transferred to the new genus Fragilonemertes. Intertidal to shallow subtidal, under stones in sand or muddy-sand, often in protected bays, harbors or estuaries, locally common in the Woods Hole region with a range extending from Massachusetts Bay to northern Florida and as far west as Texas in the Gulf of Mexico.

* Lineus pallidus Verrill, 1879

Of particularly uncertain taxonomic status, originally recorded from about 80 m depth in mud off Cape Ann, Massachusetts, one additional specimen has subsequently been dredged from sandy mud at 2 m depth in Burton’s Bay, Eastern Shore, Virginia (McCaul, 1963). Although Miner (1950: 247) noted that the species occurred "off the New England coast . . .from the tidal zone" it has not yet been found intertidally.

Lineus ruber (O. F. Müller, 1774)

Found between the upper shore intertidal to subtidal situations, on muddy sand under stones and boulders, in mussel beds, among barnacles, on rock pool and other algae, in estuarine muds and on almost any sediment with a muddy component. Tolerant of salinities as low as about 8‰. The species is common in the Woods Hole region and apparently has a circumpolar distribution in the northern hemisphere; its reported occurrence in South Africa is of dubious validity.

* Lineus viridis (O. F. Müller, 1774)

With very similar ecological requirements to, and with a parallel circumpolar distribution in the northern hemisphere as, Lineus ruber, Lineus viridis is not apparently as common a species. On the Atlantic coast of the USA it has been found at Mount Desert Island and Brandy Cove (Rogers et al., 1995) and may well appear in the Woods Hole area.

Micrura affinis (Stimpson, 1854)

Found on the lower shore to subtidal depths of 300 m or more under stones. Common off the shores of Nova Scotia and Maine, it occurs below 10 m depth off Martha’s Vineyard in the Woods Hole area.

* Micrura albida Verrill, 1879

Only known from subtidal depths of 60—280 m on mud, living in translucent tubes of tough mucus, found off the eastern seaboard of Maine and Massachusetts but not found south of Cape Cod. The generic affinities of this taxon are uncertain because its internal morphology has never been investigated.

Micrura caeca Verrill, 1895

A lower shore intertidal species found under stones or in sand. So far known only from the shores of Long Island Sound and the Woods Hole region.

Micrura dorsalis Verrill, 1892

Only a single specimen of this species has ever been found, under a stone at extreme low-water level, near Eastport, Maine. The internal anatomy remains completely unknown (Coe, 1943), and the generic affinities of the species thus cannot be ascertained.

* Micrura rubra Verrill, 1892

A northern species according to Coe (1943), found subtidally on mudat depths of about 70 m in the Bay of Fundy and off Casco Bay, Maine. Coe comments that the specific validity of the species cannot be determined until additional specimens become available for study. Although not yet recorded from the Woods Hole region, it may nevertheless occur in the area.

Parapolia aurantiaca Coe, 1895

A lower shore intertidal to subtidal species found burrowed in sand or mud. So far found only in the Woods Hole region.

* Parvicirrus dubius (Verrill, 1879)

Until recently only known intertidally under stones at Gloucester, Massachusetts, under the name Lineus dubius, Riser (1993) has obtained specimens from similar habitats or in clean coarse sand from Cape Cod to Black’s Harbor, New Brunswick, as well as a single specimen dredged from 16 m depth in Buzzards Bay.

Ramphogordius sanguineus (Rathke, 1799)

Recorded under the name Lineus socialis (Leidy, 1855) as locally common in the Woods Hole area by Coe (1943), Riser (1994) transferred it to the genus Myoisophagos but subsequently noted (Riser, 1998) that this name was invalid as a junior synonym of the genus Ramphogordius. Often gregarious, with several individuals frequently being found entwined together, the species is found intertidally under rocks and stones embedded in muddy sediments, commonly in muds blackened by decaying organic matter, or among algae. A temperate water form tolerant of gradual salinity and thermal changes (Riser, 1994), with a widespread global distribution extending from European coasts to Atlantic, Gulf and Pacific shores of North America and New Zealand. Records from Bermuda and southern Chile cannot be substantiated. Locally common in the Woods Hole area (Coe, 1943).

Tarrhomyos luridus (Verrill, 1873)

Subtidal in muddy, sandy or gravelly substrata at depths of 20—350 m, with a geographic range extending from Nova Scotia southwards to South Carolina. Coe (1943) recorded it (as Cerebratulus luridus) as common off Martha’s Vineyard, at the entrance to Buzzards Bay and at the eastern end of Long Island Sound. Riser (1993) obtained a large number of specimens, along with the holothurian Molpadia oolitica, from a soft-bottomed community dominated by a sponge species (Suberites sp.) in Cape Cod Bay.

Tenuilineus bicolor (Verrill, 1892)

Previously recorded as common from the Woods Hole area under the name Lineus bicolor but redescribed and transferred to the genus Tenuilineus by Riser (1993). Rarely found intertidally, more often subtidal at depths of 2—40 m or more on shelly or stony substrata among hydroids, algae and ascidians. Its known range extends from Cape Cod southwards on the Atlantic seaboard of the USA.

Zygeupolia rubens (Coe, 1895)

Lower shore intertidal to subtidal depths of 50 m, burrowed in sand or under stones on sand in bays, estuaries and harbors. Reported from the Atlantic (southern New England, Maine and southwards) and Pacific (California to Ensenada, Mexico) coasts of North America, locally abundant in the Woods Hole region.

CLASS ENOPLA

Subclass Hoplonemertea

Superorder Monostilifera

Amphiporus angulatus (O. F. Müller, 1774)

Intertidal under stones on sand or subtidally to depths of 150 m or more, the zoogeographic distribution of this species is uncertain because of the taxonomic confusion surrounding specimens identified as belonging to this taxon. Originally reported from Greenland, Coe (1943) recorded it from Nova Scotia, New England to Cape Cod and farther south underneath the offshore Arctic current off the Atlantic coast of North America; the species has supposedly also been found at Baffin Bay, Davis Strait and Labrador, on the Pacific coast (California to Alaska) and in the Bering Strait, the Aleutian Islands and off the shores of the Kamchatka Peninsula and Japan. Riser (1993) notes that the species does not belong in the genus Amphiporus and could readily be transferred to the genus Cyanophthalma, but that the potential value of certain morphological features indicate that such a transfer should not be made until the morphology of certain other, possibly related, ‘Amphiporus’ species have been investigated.

Amphiporus bioculatus McIntosh, 1873—74

Gibson (1995) notes that taxonomic confusion surrounds records for this species, Gibson and Crandall (1989) regarding it as a nomen dubium; whether the Woods Hole species belongs to this or some other genus remains uncertain. Coe (1943) recorded it as occurring subtidally on sandy and shelly substrata at depths of 2—35 m along the coast of New England, and as being locally common in Vineyard Sound and near Woods Hole.

* Amphiporus caecus Verrill, 1892

Subtidal from 33—37 m depth, recorded from Block Island, Massachusetts and Rhode Island Sound; the species has also supposedly been found in the Beagle Canal, Tierra del Fuego (Isler, 1902). Not a well described taxon, listed by Gibson and Crandall (1989) as a nomen dubium. Although not yet recorded from the Woods Hole area it may well occur in the region.

Amphiporus cruentatus Verrill, 1879

Lower shore to subtidal depths of 80 m or more, among kelp holdfasts, algae, hydroids and other growths on pier pilings and rocks, or on shelly substrata. Locally common in the Woods Hole region, with a distribution extending from New England to Florida on the Atlantic seaboard and Puget Sound to southern California on the Pacific seaboard.

* Amphiporus frontalis Verrill, 1892

An inadequately described intertidal species found near low water level at Eastport, Maine, listed as a nomen dubium by Gibson and Crandall (1989).

* Amphiporus glutinosus (Verrill, 1873)

Coe (1943) included this form as a junior synonym for Amphiporus griseus (Stimpson, 1855), but Gibson and Crandall (1989) listed it under the name Amphiporus glutinosus as a nomen dubium because of doubts over the conspecificity of Verrill’s (1873) and Montgomery’s (1897) descriptions of this taxon. Found intertidally to subtidal depths of about 12 m, in rock pools, creeping among algae or hydroids, on muddy, sandy, shelly or gravelly substrata, on buoys and pilings of bridges or wharves, also occurring in brackish water among oyster or eelgrass beds. So far reported only from the coasts of Massachusetts and Connecticut, but may possibly occur in the Woods Hole area.

* Amphiporus greenmani Montgomery, 1897

Intertidal among algae, only certainly known from Ludlam Bay, Sea Isle, New Jersey. Coe (1943) synonymized the species with Amphiporus ochraceus (Verrill, 1873) but Gibson and Crandall (1989) retained it as a distinct species inquirenda.

Amphiporus griseus (Stimpson, 1855)

Lower shore intertidal to subtidal on sand flats, among bryozoans and hydroids, often with algae and eelgrasses, sometimes under stones. Occasionally found in the Woods Hole area, the range extends from New England southwards to Florida. Gibson and Crandall (1989) noted that Amphiporus griseus sensu Coe, 1943, may be synonymous with Amphiporus glutinosus sensu Montgomery, 1897.

* Amphiporus hastatus McIntosh, 1873—74

Intertidal to subtidal depths of about 14 m, among laminarian holdfasts attached to mussels or in sand. The zoogeographic distribution of this taxon remains uncertain because of the confusion surrounding its identity; Verrill (1875) recorded it from Block Island Sound, New England, whereas Girard (1893) listed it under the name Hallezia hastata, but Bürger (1904) included Girard’s species as in part synonymous with McIntosh’s form, in part with Amphiporus caecus. Coe (1943) makes no mention of the species.

* Amphiporus heterosorus Verrill, 1892

Subtidal from depths of 20—400 m on sand or mud, recorded from the coasts of the Bay of Fundy and Maine. Coe (1943) includes the form as synonymous with Amphiporus angulatus but Gibson and Crandall (1989) retain it under its original name, as a nomen dubium, because there are no anatomical data to confirm a synonymy between the two taxa.

* Amphiporus lactifloreus (Johnston, 1828)

Intertidal to subtidal depths of 250 m or more, under stones on fairly clean sand or gravelly-sand, on brown algae or amongst shell debris, less commonly in silt or mud. The species has a wide distribution in the northern hemisphere, ranging from the Mediterranean and northern coasts of Europe to Arctic and Atlantic coasts of North America. A report of the species from Japan is considered to be a dubious validity. Coe (1943) records the species as common on the Maine coast, but not extending south of Cape Cod.

* Amphiporus mesosorus Verrill, 1892

Coe (1943) included this form as a synonym of Amphiporus (now Nipponnemertes) pulcher but Berg (1985) doubted this. Gibson and Crandall (1989) included the species, as a nomen dubium, under its original name. Only so far found subtidally in Massachusetts Bay.

* Amphiporus multisorus Verrill, 1892

Lower shore intertidal to subtidal depths of about 25 m, so far known only from Eastport, Maine. Included as a synonym of Amphiporus angulatus by Coe (1943), but listed as a nomen dubium under its original name by Gibson and Crandall (1989).

Amphiporus ochraceus (Verrill, 1873)

Intertidal and subtidal to depths of about 36 m, under stones, among algae, bryozoans, hydroids, mussels and other growths on rocks, piers or antifouling panels, or on muddy, sandy, gravelly or rocky bottoms, often in protected bays and sometimes extending into brackish waters. Locally common around Woods Hole, with a distribution ranging from Massachusetts southwards to Florida. Coe (1943) notes that south of Cape Cod it is the most abundant member of this genus.

* Amphiporus stimpsoni (Stimpson, 1854)

Lower shore intertidal under stones, recorded from the Bay of Fundy and Maine. Verrill (1892) and Coe (1943) included the form as synonymous with Amphiporus angulatus, but Gibson and Crandall (1989) retained it under its original name as a nomen dubium.

* Amphiporus tetrasorus

Found off Cape Ann, Massachusetts, on mud at a depth of about 80 m and listed by Coe (1943) as a northern species not reported south of Cape Cod.

Carcinonemertes carcinophila (Kölliker, 1845)

Variously described as an ectosymbiont, specialist egg-predator or ectoparasite of decapod crustaceans, Coe (1943) notes that in the Woods Hole area the most frequent host is the lady crab Ovalipes ocellatus. The species is typically found on and among the eggs of berried female crabs or on their gills; Wickham and Kuris (1985) list 28 species of crabs reported as hosts to this nemertean.

Cyanophthalma cordiceps (Friedrich, 1933)

First recorded as Tetrastemma vittata from muddy bottoms off the New England coast by Verrill (1874), Coe (1943) listed the taxon as occasionally being found in muddy situations around the Woods Hole area, with a range extending from the Bay of Fundy southwards to Long Island Sound, creeping sluggishly on mud, or on eelgrasses, shells or other materials near low water intertidally to subtidal depths of 45 m, usually in protected harbors. Norenburg (1986: 275), commenting that Brunberg (1964) suspected that Verrill’s taxon was synonymous with Amphiporus cordiceps (Jensen, 1878), a supposition confirmed by Riser in Norenburg’s paper, listed "Amphiporus cordiceps (Jensen, 1878) (sensu Friedrich 1933, 1935a) [as] referred to Cyanophthalma."

Cyanophthalma obscura (Schultze, 1851)

In salt marshes or salt marsh pools, brackish water intertidal, recorded from the Baltic and Black Seas and on the eastern North American coast from Nova Scotia to New England and Maine (Norenburg, 1986).

Emplectonema giganteum (Verrill, 1873)

Found on sandy or muddy substrata at depths of 120—1500 m or more, with a distribution extending off the coasts of Nova Scotia southwards to the Gulf of Maine and Nantucket and Block Island, Massachusetts. Coe (1943) noted that it was common near Sable Island.

* Nipponnemertes pulchra (Johnston, 1837)

Listed under the name Amphiporus pulcher as a northern species not recorded south of Cape Cod by Coe (1943), the species was transferred to the genus Nipponnemertes by Berg (1972). Occasionally found intertidally but much more common subtidally to depths of 200 m or more in sandy, gravelly or stony sediments or among coralline algae. The species is widespread in the northern hemisphere, with a distribution extending from the east coast of North America to the Atlantic coasts of France and Scandinavia. Records from the southern hemisphere are of uncertain validity.

Oerstedia dorsalis (Abildgaard, 1806)

Intertidal to subtidal depths of 80 m or more, typically on small algae in rock pools, under stones or among fucoid or laminarian holdfasts, on a wide range of substrata below tide levels (mud, sand, gravel, stones or shells), occasionally among ascidians or on the hulls of sunken vessels. The species is extremely variable in color pattern, with at least seven described varieties; future studies must determine which of the varieties, if any, warrant specific status. Locally abundant in the Woods Hole area (Coe, 1943), Oerstedia dorsalis has been reported as widely distributed in the northern hemisphere, from the Black Sea and Mediterranean westwards to Atlantic, North sea and Baltic coasts of north-western Europe, Atlantic, Gulf and Pacific coasts of North America and Japan.

Ototyphlonemertes pellucida Coe, 1943

Intertidal to shallow subtidal among algae or in coarse sand. Known only from the Atlantic coast of the USA from New England (Cape Cod) southwards to Florida. A small interstitial species, often found in protected harbors.

* Proneurotes multioculatus Montgomery, 1897

Lower shore intertidal among hydroids growing on pier pilings, so far known only from Sea Isle, New Jersey.

Prostoma sp.

Coe (1943) recorded that a freshwater species, Prostoma rubrum (Leidy, 1850), was commonly found in several ponds in the Woods Hole area and was widely distributed within the USA from New England to Florida and westwards to Washington and California. Gibson and Moore (1976), however, concluded that the species was inadequately described and could not be accepted as a valid taxon; the specific identity of the Woods Hole Prostoma thus remains uncertain.

Tetrastemma candidum (O. F. Müller, 1774)

Mid-shore intertidal to subtidal depths of 55 m or more, among rock pool algae or eelgrasses, with hydroid colonies, in old polychaete tubes, under rocks or in shelly gravel or sand. Coe (1943) reports the species as locally common in the Woods Hole region. The species supposedly possesses a circumpolar distribution in the northern hemisphere, and has also been reported from Brazil and South Africa, but different author’s descriptions are far from being in agreement and many records relating to the species are of uncertain validity.

Tetrastemma elegans (Girard, 1852)

Lower shore and subtidal to depths of about 15 m among bryozoans, algae and other growths on pier pilings and rocks, among eelgrasses or on shelly substrata. Occasionally found in the Woods Hole area, the distribution extends from the southern coast of Cape Cod southwards to at least Chesapeake Bay.

Tetrastemma vermiculus (Quatrefages, 1846)

Lower shore intertidal to subtidal depths of 40—60 m, under rocks and stones, among bryozoans, hydroids, ascidians and algae on rocks or pier pilings, or in laminarian holdfasts. Common in the Woods Hole region (Coe, 1943), with a wide zoogeographic distribution extending from the Mediterranean and Atlantic coasts of north-western Europe, Madeira, the eastern seaboard of the USA (Bay of Fundy to Florida) and the Gulf of Mexico. Three subspecies have been recorded, but the species itself is poorly described.

Tetrastemma verrilli (Bürger, 1904)

Subtidal from a depth of 40 m, dredged off Block Island. Coe (1943) comments that additional material must be studied before the status of this species can be ascertained.

Tetrastemma wilsoni Coe, 1943

Subtidal among sponges, bryozoans and other growths on pier pilings, known only from the Woods Hole region (Coe, 1943).

Zygonemertes virescens (Verrill, 1879)

Lower shore intertidal to subtidal depths of 20—120 m, among algae, hydroids, ascidians, mussels and other growths on rocks and pier or wharf pilings. Common in the Woods Hole region (Coe, 1943), the distribution ranges from the Bay of Fundy to Florida on the Atlantic coast of North America, and from British Columbia to Mexico on thePacific coast; it is also recorded from the Gulf of Mexico and Curaçao.

Subclass Bdellonemertea

Malacobdella grossa (O. F. Müller, 1776)

Marine, entocommensal in the mantle cavity of bivalve molluscs. At least 23 host species have been reported; not usually common in the Woods Hole area (Coe, 1943), hosts include Mya arenaria, Mercenaria mercenaria and, less frequently, Ostrea virginica. The nemertean is widespread on northern coasts of Europe and has also been reported from the Mediterranean, Iceland and Atlantic (Nova Scotia to the Gulf of Mexico) and Pacific (Puget Sound to California) coasts of North America. Malacobdella mercenaria Verrill, 1873, and Malacobdella obesa Verrill, 1873, have both been synonymized with Malacobdella grossa but Kozloff (1991) notes that these synonymies need to be supported by further studies.

Key to the Nemerteans of the Woods Hole region

This key is based entirely upon features distinguishable in living specimens, its use requiring neither a detailed knowledge of the animals nor any equipment more elaborate than a low-power binocular microscope or good hand lens. With the systematics of the phylum being primarily based on internal morphology, such a key inevitably has some limitations; it has nevertheless been intentionally devised to exclude the need for histological examination.

| 1A. Marine |

Click thumbnails to enlarge

|

2 |

| 1B. Freshwater |

|

Prostoma sp. |

| |

|

|

| 2A Free-living |

|

4 |

| 2B. Species either living as commensals in mantle cavity of bivalve molluscs or as ectosymbiont/specialist egg predators on egg masses or between the gill filaments of crabs |

|

3 |

| |

|

|

| 3A. Found on crabs; small, slender nemerteans, adults brick red or orange, juveniles yellowish or pinkish-red; with 2 small ocelli; without posterior sucker |

|

Carcinonemertes carcinophila |

| 3B.Found living in mantle cavity of bivalve molluscs; without ocelli; with posterior ventral sucker |

|

Malacobdella grossa |

| |

|

|

| 4A.Head with distinct longitudinal lateral cephalic slit or furrow on each side (Fig. 1) |

|

5 |

| 4B.Head without lateral cephalic slits, either without slits or furrows at all or with 1 or 2 pairs of transverse or oblique grooves (Fig. 2) |

|

9 |

| |

|

|

| 5A.Without caudal cirrus |

|

6 |

| 5B.With caudal cirrus (Fig. 3) |

|

10 |

| |

|

|

| 6A.Head with ocelli (N.B. ocelli may be partially masked in species with darker cephalic pigmentation) |

|

7 |

| 6B.Head without ocelli; color whitish or pale yellow, anteriorly with a reddish tinge, somewhat indistinctly paler in mid-dorsal line; with 2 pale dorsal spots at rear of yellowish head |

|

Lineus pallidus |

| |

|

|

| 7A.Color variable but distinctly reddish-brown or dull brown |

|

8 |

| 7B.Color variable but distinctly greenish or almost black |

|

9 |

| |

|

|

| 8A.With 2—8 ocelli on either side of head; color typically light to dark reddish-brown, paler ventrally, sometimes with greenish-red, yellowish-brown or violet tinge; when mechanically stimulated worm contracts straight, not coiling into tight spiral |

|

Lineus ruber |

| 8B.With 4—6 ocelli on each side of head; color varying from light reddish-brown to dull brown, often paler posteriorly and ventrally; when mechanically stimulated worm contracts into tight spiral |

|

Ramphogordius sanguineus |

| |

|

|

| 9A.Head with row of 2—8 ocelli on each side; dorsal color pale to dark green or olive-green, greenish-black, deep bronze green or almost black, often shading from darker anteriorly to paler posteriorly, ventrally paler; pale transverse lines usually distinguishable along full length of body behind head; gonopores white in sexually mature individuals |

|

Lineus viridis |

| 9B. Head with an, often irregular, row of 4—7 ocelli on each side; dorsally dark green, brownish-green or yellowish-green, with conspicuous mid-dorsal whitish or pale yellow longitudinal stripe, ventral surface pale green or yellowish-white |

|

Tenuilineus bicolor |

| |

|

|

| 10A.With ocelli |

|

11 |

| 10B.Without ocelli |

|

12 |

| |

|

|

| 11A.Caudal cirrus distinct but slender; head with a row of 4—6 dark ocelli on each side; color deep red, reddish-brown or greenish-brown, often with pale, narrow and indistinct transverse lines, paler ventrally; margins of head whitish |

|

Micrura affinis |

| 11B. Caudal cirrus distinct; head with row of about 12 white ocelli on each side; color light to dark olive green |

|

Parvicirrus dubius |

| |

|

|

| 12A.Body firm, intestinal region wide, distinctly flattened, with thin, sharp lateral margins |

|

13 |

| 12B.Body soft, intestinal region somewhat flattened, but slender, without thin, sharp lateral margins |

|

14 |

| |

|

|

| 13A.Juveniles translucent white, with pale yellow or brown intestinal diverticula visible through body wall, adults yellowish-white to pinkish, sexually mature females a dull brownish-red, males deep red |

|

Cerebratulus lacteus |

| 13B.Dorsal color slate-grey, drab olive green or greyish-brown, ventral surface paler |

|

Cerebratulus marginatus |

| |

|

|

| 14A.Overall color whitish or pale yellow, often tinged reddish anteriorly; also reported as milk-white with distinct narrow blue band at the rear of the head |

|

Micrura albida |

| 14B.Not as above |

|

15 |

| |

|

|

| 15A.General color pale yellow, anteriorly tinged orange, with distinct, broad median dorsal and ventral longitudinal dark stripes |

|

Micrura dorsalis |

| 15B.Overall color variable but not marked with distinct dorsal and ventral longitudinal stripes |

|

16 |

| |

|

|

| 16A.Overall color white or paler shades of yellow, red or brown |

|

17 |

| 16B.Overall color a dark reddish or brownish |

|

18 |

| |

|

|

| 17A.Pale red, brownish-red or yellowish-red |

|

Micrura caeca |

| 17B.Pale orange-red, flesh colored or bright red; intestinal region often irregularly mottled due to gonads and intestinal diverticula |

|

Micrura rubra |

| |

|

|

| 18A.Body color deep red or purplish-red, tip of head and surroundings of mouth whitish |

|

Fragilonemertes rosea |

| 18B.Body color dark olive, chocolate, reddish- or purplish-brown; younger individuals paler |

|

Tarrhomyos luridus |

| |

|

|

| 19A.With ocelli |

|

20 |

| 19B.Without ocelli |

|

46 |

| |

|

|

| 20A.With less than 9 ocelli |

|

21 |

| 20B. With 10 or more ocelli, usually 12—15, sometimes with many more |

|

29 |

| |

|

|

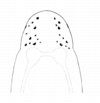

| 21A.With 2 large ocelli located near the tip of the head (Fig. 4) |

|

Amphiporus bioculatus |

| 21B.With more than 2 ocelli |

|

22 |

| |

|

|

| 22A.With 4 single-cup ocelli arranged to form corners of a square or rectangle (in some specimens ocellar fragmentation may produce more than 4 ocelli, but each remains a single-cup type); ocelli black or brown (Fig. 5) |

|

23 |

| 22B.With 4 double-cup ocelli (in newly released juveniles the anterior ocelli are single); ocelli navy-blue |

|

28 |

| |

|

|

| 23A.Dorsally marked with 2 broad longitudinal brown stripes extending more or less full body length of body, with narrow brown stripes between anterior and posterior ocelli on either side of head, or variably mottled, banded, spotted or striped |

|

24 |

| 23B.Color variable but without obvious color pattern |

|

26 |

| |

|

|

| 24A.Color pattern confined to dorsal surface of head, comprising narrow dark brown streak joining anterior and posterior ocelli on each side of head; general body color dull whitish, salmon-pink, pale orange or apricot yellow (Fig.6) |

|

Tetrastemma vermiculus |

| 24B.Color pattern extending over most or all of dorsal surface |

|

25 |

| |

|

|

| 25A.General body color yellow, dorsally marked by 2 broad brown longitudinal stripes separated by narrow but sharply defined median yellow stripe (in juveniles brown stripes may be replaced by 2 rows of brown spots) |

|

Tetrastemma elegans |

| 25B.Color pattern variable, with median yellow or whitish longitudinal stripe, often extending along entire, or irregularly interrupted, or marbled, spotted or transversely banded with pale yellowish-brown, reddish-orange, dark brown or brilliant white on a pale yellowish to brownish background |

|

Oerstedia dorsalis |

| |

|

|

| 26A.Body color bright rosy red |

|

Tetrastemma verrilli |

| 26B.Body color variable, translucent or milky white or in pale shades of yellow, orange, red, brown or green |

|

27 |

| |

|

|

| 27A.Body color variably pale dull yellow, orange, brown or green, sometimes with an opaque white patch between eyes; cephalic furrows sometimes with brownish pigmentation |

|

Tetrastemma candidum |

| 27B.Body color translucent or milky white, very pale yellow or with a tinge of red, dorsally covered by scattered flecks of opaque white |

|

Tetrastemma wilsoni |

| |

|

|

| 28A.Dorsum of body yellowish-brown to dark olive-green, paler ventrally, without pattern of radiating stripes on head |

|

Cyanophthalma obscura |

| 28B.Body olive-green with 6 short yellow stripes radiating from tip of head (rarely brownish with violet stripes) (Fig.7) |

|

Cyanophthalma cordiceps |

| |

|

|

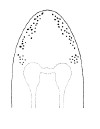

| 29A.Ocelli numbering 80 or more on each side of the head, forming elongate clusters or irregular rows extending full length of head, continuing posterior of brain as single row along each lateral margin (juveniles < 1 mm long with only 4 ocelli) (Fig. 8) |

|

Zygonemertes virescens |

| 29B.Ocelli confined entirely to head region, not extending behind brain |

|

30 |

| |

|

|

| 30A.Ocelli on either side of head arranged into 2 distinct and separate groups (Fig. 9) |

|

31 |

| 30B.Ocelli on either side of head not arranged in 2 obviously separate groups, either forming 1 or more than 3 groups or irregularly distributed |

|

37 |

| |

|

|

| 31A.Head with 2 pairs of cephalic furrows extending on to dorsal surface, posterior pair usually meeting medially forming V-shape |

|

32 |

| 31B.Head with 1 pair of inconspicuous oblique ventral cephalic furrows and 1 pair of shallow longitudinal dorsal grooves towards rear of head; ocelli on each side of head arranged into an elongate anterolateral cluster of 20-30 large ocelli and a rounded cerebral (posterior) group of 8—12 smaller ocelli near front of brain; bright orange or deep salmon-pink dorsally, flesh colored ventrally (Fig. 10) |

|

Emplectonema giganteum |

| |

|

|

| 32A. Anterior pair of cephalic furrows with obvious anteriorly directed parallel ridges running at right angles to transverse furrows; head with median dorsal longitudinal ridge or swelling; ocelli on each side of head arranged into more or less single anterolateral marginal row of 10-20 and a more compact cerebral group of 10-20 close to brain, smaller individuals with fewer but larger ocelli; orange or red dorsally, paler ventrally (Fig. 11) |

|

Nipponnemertes pulchra |

| 32B.Anterior pair of cephalic furrows without parallel ridges running at right angles to them |

|

33 |

| |

|

|

| 33A.Color creamy-white to pink-red, orange or yellowish-red (green variety found near Woods Hole); ocelli on each side of head arranged into single anteromarginal group of about 5 connected with an oblique row extending posteriorly and medially along front margin of anterior cephalic furrow, and posterior group of 7-9 ocelli forming an irregular double row parallel with the posterior margin of the anterior cephalic furrow (Fig. 12) |

|

Proneurotes multioculatus |

| 33B.Not as above |

|

34 |

| |

|

|

| 34A.Dorsal body color distinctly darker than ventral |

|

35 |

| 34B.Dorsal and ventral body coloration similarly dull pinkish or dirty white, although intestinal region may be orange to reddish in mature females, light brown to pale grey in males, and gut contents at any time of year may give intestine a dark grey, brownish or greenish tinge; ocelli on each side of head arranged into marginal anterior row or cluster of 8-10, posterior cerebral cluster of 3-10 close in front of pinkish brain (Fig. 13) |

|

Amphiporus lactifloreus |

| |

|

|

| 35A.General dorsal color chocolate-brown, darker in mid-line, tip of head and ventral surface white; numerous ocelli forming 2 oblique clusters parallel with cephalic furrows on either side of head (Fig. 14) |

|

Amphiporus tetrasorus |

| 35B.Not as above |

|

36 |

| |

|

|

| 36A.Dorsum of body cherry-red, clear reddish-brown or pale chocolate-brown, laterally and ventrally flesh-colored; head with dark median longitudinal line; ocelli numerous, on each side of head arranged into anterior triangular cluster and posterior rounded cluster (Fig. 15) |

|

Amphiporus heterosorus |

| 36B.Dorsum of body dark brown, reddish-brown, purple-brown or purple, ventrally whitish, pink, pale brown or grey with a tinge of purple; ocelli arranged into elongate anterolateral group of 12-20 rather large ocelli and cerebral group of 8-15 smaller ocelli on each side of head (Fig. 16) |

|

Amphiporus angulatus |

| |

|

|

| 37A.Head with only 1 pair of cephalic furrows which both dorsally and ventrally meet in mid-line forming anteriorliy directed V-shape; dorsal surface of head with pale longitudinal median ridge; overall color pinkish, yellow-brown, pale brown, dark greyish-brown or bright reddish (Fig. 17) |

|

Amphiporus hastatus |

| 37B.Head with 2 pairs of cephalic furrows |

|

38 |

| |

|

|

| 38A.Ocelli large, black and distinct, arranged as irregular double row of 6-10 on each anterolateral margin of head but not extending behind anterior pair of cephalic furrows; overall color pale grey, yellowish, salmon-pink or flesh, darker mid-dorsally but not forming precisely defined longitudinal stripe (Fig. 18) |

|

Amphiporus frontalis |

| 38B.Ocellar arrangement variable, but some always present behind anterior pair of cephalic furrows |

|

39 |

| |

|

|

| 39A.Ocelli on each side of head arranged into 3 small anterior clusters of 3-4 each, with 2 rounded cerebral groups of 6-8 each near front of brain; overall salmon-pink or flesh colored, paler ventrally (Fig. 19) |

|

Amphiporus multisorus |

| 39B.Ocelli not as above |

|

40 |

| |

|

|

| 40A.Ocelli on each side of head arranged into 1 or more rows, not forming clusters or groups |

|

41 |

| 40B.Ocelli on each side of head irregularly scattered and/or arranged into groups |

|

45 |

| |

|

|

| 41A.Ocelli arranged into single row on either side of head |

|

42 |

| 41B.Ocelli arranged into 2 or 3 rows on each side of head |

|

43 |

| |

|

|

| 42A.Head with 6 or more minute ocelli arranged in single oblique anterior row on either side; dorsum of body brown, head with white margin bearing elongate white patch on either side and narrow convex white band crossing dorsal surface (Fig. 20) |

|

Amphiporus stimpsoni |

| 42B.Head with 5-10 well separated ocelli arranged in single lateral row on either side, with anterior ocellus distinctly larger than others in row; body typically pale yellow, less often whitish, sometimes light pink, reddish or orange anteriorly; bright red coloration of blood corpuscles making 3 longitudinal blood vessels very conspicuous in life (Fig. 21 |

|

Amphiporus cruentatus |

| |

|

|

| 43A.With 3 diverging oblique rows, each of 2-4 ocelli, on either side of head; body dull yellow to pale orange-yellow, sometimes brighter orange anteriorly, paler posteriorly with faint dusky or greenish median line (Fig. 22) |

|

.Amphiporus glutinosus |

| 43B.Not as above |

|

44 |

| |

|

|

| 44A.Each side of head with 8-12 large ocelli arranged in 2 rows, not posteriorly reaching brain; overall color transparent creamy-white or pinkish (Fig. 23) |

|

Amphiporus greenmani |

| 44B.Head with 6-14 ocelli arranged into several short divergent rows on either side, anterior and posterior ocelli distinctly larger than others; body color yellow or cream, anteriorly pale to deep orange (Fig. 24) |

|

Amphiporus ochraceus |

| |

|

|

| 45A.Head with 7-12 ocelli either irregularly scattered or loosely arranged into more or less parallel oblique rows on either side of head; overall whitish, pale yellow or pale orange-yellow; worms secreting very sticky mucus when handled (Fig. 25) |

|

.Amphiporus griseus |

| 45B.Each side of head with numerous ocelli arranged into large, irregular, somewhat triangular group with apex directed posteriorly, sometimes appearing as a rounded cerebral cluster joining into a short anterior triangular group; bright red dorsally, flesh-colored ventrally (Fig. |

|

Amphiporus mesosorus |

| |

|

|

| 46A.Head with 1 or 2 pairs of oblique cephalic furrows |

|

47 |

| 46B.Head without cephalic furrows |

|

48 |

| |

|

|

| 47A.With 1 pair of oblique cephalic furrows; overall color bright orange, head paler |

|

Parapolia aurantiaca |

| 47B.With 2 pairs of oblique cephalic furrows; bright reddish-orange with darker red median dorsal longitudinal stripe, lateral margins paler yellowish-orange |

|

Amphiporus caecus |

| |

|

|

| 48A.Without caudal cirrus |

|

49 |

| 48B.With long caudal cirrus; head very long and sharply pointed, head white, body pale rose-red, flesh-colored or pale yellowish-red, caudal cirrus white; young specimens may be completely white |

|

Zygeupolia rubens |

| |

|

|

| 49A.Head long, body very slender, mouth located far behind brain (Fig. 27) |

|

50 |

| 49B.Head broad or slender, mouth either close behind brain or not separate from proboscis pore |

|

51 |

| |

|

|

| 50A.Body slender and threadlike, whitish, grey, pale yellow or a light pinkish-red, often with a rosy, greenish or salmon-pink tint posteriorly; young almost colorless, with 2 minute ocelli, these present in adults; body coiling into tight spiral when contracted |

|

Procephalothrix spiralis |

| 50B.Body slender, threadlike, white, usually with yellowish tinge anteriorly; juveniles with 2 minute black eyes, these absent in adults; body not coiling into tight spiral when contracted |

|

Cephalothrix linearis |

| |

|

|

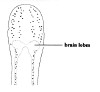

| 51A.Body minute, slender, translucent; brain with pair of spherical statocysts in ventral ganglia (Fig. 28) |

|

Ototyphlonemertes pellucida |

| 51B.Brain without statocysts |

|

52 |

| |

|

|

| 52A.Body rounded anteriorly, flattened in intestinal region |

|

53 |

| 52B.Body rounded throughout, very slender, head and foregut regions pure white or translucent, becoming an opaque white to cream posteriorly; in sexually ripe individuals pale yellow or orange median longitudinal dorsal stripe may be evident |

|

Tubulanus pellucidus |

| |

|

|

| 53A.General color milk white and more or less translucent, although intestinal region may appear yellowish or brownish due to gut contents; head without median row of sensory pit2 |

|

Carinomella lactea |

| 53B.General color pale reddish or yellowish, head and foregut regions often white or with pale reddish tint; intestinal region pale yellow, reddish or pale brown; head with median dorsal row of sensory pits |

|

Carinoma tremaphoros |

Selected References on Nemertea

Berg, G. 1972. Studies on Nipponnemertes Friedrich, 1968 (Nemertini, Hoplonemertini). I. Redescription of Nipponnemertes pulcher (Johnston, 1837) with special reference to intraspecific variation of the taxonomical characters. Zool. Scr. 1: 211-225.

Berg, G. 1985. Studies on Nipponnemertes Friedrich (Nemertini, Hoplonemertini). II. Taxonomy of Nipponnemertes pulcher (Johnston) and some other species. Zool. Scr. 14: 239-246.

Boesch, D. F. 1973. Classification and community structure of macrobenthos in the Hampton Roads area, Virginia. Mar. Biol. 21: 226-244.

Brunberg, L. 1964. On the nemertean fauna of Danish waters. Ophelia 1: 77-111.

Bürger, O. 1904. Nemertini. Tierreich 20: 1-151.

Coe, W. R. 1905. Nemerteans of the west and northwest coasts of America. Bull. Mus. Comp. Zool. Harvard 47: 1-318.

Coe, W. R. 1943. Biology of the nemerteans of the Atlantic coast of North America. Trans. Conn. Acad. Arts Sci. 35: 129-328.

Corrêa, D. D. 1961. Nemerteans from Florida and Virgin Islands. Bull. Mar. Sci. Gulf Carib. 11: 1-44.

Gibson, R. 1972. Nemerteans. London, Hutchinson, 224 pp.

Gibson, R. 1994. Nemerteans. Shrewsbury, Field Studies Council, 224 pp (Synopses of the British Fauna [New Series] No. 24, 2nd edition)

Gibson, R. 1995. Nemertean genera and species of the world: an annotated checklist of original names and description citations, synonyms, current taxonomic status, habitats and recorded zoogeographic distribution. J. Nat. Hist. 29: 271-562.

Gibson, R. and Crandall, F. B. 1989. The genus Amphiporus Ehrenberg (Nemertea, Enopla, Monostiliferoidea). Zool. Scr. 18: 453-470.

Gibson, R. and Moore, J. 1976. Freshwater nemerteans. Zool. J. Linn. Soc. 58: 177-218.

Girard, C. 1893. Recherches sur les Planariés et les Némertiens de l’Amérique du Nord. Annals Sci. Nat., Zool. 15: 145-310.

Isler, E. 1902. Die Nemertinen der Sammlung Plate. Zool. Jb., Suppl. 5 (Fauna Chilensis 2): 273-280.

Kirsteuer, E. 1967. Marine, bethonic nemerteans: how to collect and preserve them. Am. Mus. Novit. No. 2290: 1-10.

Kozloff, E. N. 1991. Malacobdella siliquae sp. nov. and Malacobdella macomae sp. nov., commensal nemerteans from bivalve molluscs on the Pacific coast of North America. Can. J. Zool. 69: 1612-1618.

Mackey, L. Y., Winnepenninckx, B., De Wachter, R., Backeljau, T., Emschermann, P. and Garey, J. R. 1996. 18S rRNA suggests that Entoprocta are protostomes, unrelated to Ectoprocta. J. Mol. Evol. 42: 552-559.

McCaul, W. E. 1963. Rhynchocoela: nemerteans from marine and estuarine waters of Virginia. J. Elisha Mitchell Sci. Soc. 79: 111-124.

Miner, R. W. 1950. Field book of seashore life. New York, Putnam, 888 pp.

Montgomery, T. H. 1897. Descriptions of new metanemerteans, with notes on other species. Zool. Jb. Syst. 10: 1-14.

Norenburg, J. 1986. Redescription of a brooding nemertine, Cyanophthalma obscura (Schultze) gen. et comb. n., with observations on its biology and discussion of the species of Prostomatella and related taxa. Zool. Scr. 15: 275-293.

Riser, N. W. 1993. Observations on the morphology of some North American nemertines with consequent taxonomic changes and a reassessment of the architectonics of the phylum. Hydrobiologia 266: 141-157.

Riser, N. W. 1994. The morphology and generic relationships of some fissiparous hetero-nemertines. Proc. Biol. Soc. Wash. 107: 548-556.

Riser, N. W. 1998. The morphology of Micrura leidyi (Verrill, 1892) with consequent systematic revaluation. Hydrobiologia 365: 149-156.

Rogers, A. D., Thorpe, J. P. and Gibson, R. 1995. Genetic evidence for the occurrence of a cryptic species with the littoral nemerteans Lineus ruber and L. viridis (Nemertea: Anopla). Mar. Biol. 122: 305-316.

Scheltema, A. H. 1993. Aplacophora as progenetic aculiferans and the coelomate origin of mollusks as the sister taxon of Sipuncula. Biol. Bull. 184: 57-78.

Sundberg, P. 1991. A proposal for renaming the higher taxonomic categories in the phylum Nemertea. J. Nat. Hist. 25: 45-48.

Verrill, A. E. 1873. Report upon the invertebrate animals of Vineyard Sound and the adjacent waters, with an account of the physical characters of the region. Rep. U.S. Comm. Fish., Part I: 295-778

Verrill, A. E. 1874. Brief contributions to Zoology from the Museum of Yale College. No. XXVI. Results of recent dredging expeditions on the coast of New England. Amer. J. Sci., Series 3, vol. 7: 38-46.

Verrill, A. E. 1875. Brief contributions to Zoology from the Museum of Yale College. No.. XXXIII. Results of dredging expeditions off the New England coast in 1874. Amer. J. Sci., Series 3, vol. 10: 36-43.

Verrill, A. E. 1892. The marine nemerteans of New England and adjacent waters. Trans. Conn. Acad. Arts Sci. 8: 382-456.

Wickham, D. E. and Kuris, A. M. 1985. The comparative ecology of nemertean egg predators. Amer. Zool. 25: 127-134.

Zrzav_, J., Mihulka, S., Kepka, P., Bezdek, A. and Tietz, D. 1998. Phylogeny of the Metazoa based on morphological and 18S ribosomal DNA evidence. Cladistics 14: 249—285.

|